The erosion of ‘institutional guardrails’

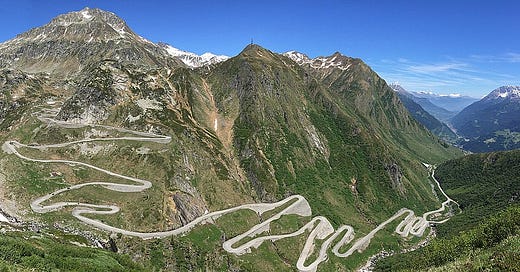

Imagine you’re driving along a treacherous road, like one of the routes I often had to take in the Swiss Alps, the ones that have signs warning of cows falling from the sky above you. The route up the mountain is fine – good enough. You’re lucky. You’re on the cow side, hugging the mountain. What you really need to worry about are the cars coming at you down the mountain. Their drivers keep veering towards and often over the central line. Because the other side of the road is the edge, with nothing to break their descent for a thousand metres.

In both public and corporate governance today, there are a lot of dangers, from the chasms below and the cows above. Let’s look at the metaphor.

The rule of law is an institutional guardrail. And we worry that much of the political campaign in America, the politics of countries in Europe, and the problems things like social media and artificial intelligence pose to society suggest the foundations of the guardrail is eroding, and no one is out conducting the maintenance work that the Swiss do, like clockwork, on their roads.

Let’s think about institutions, how they keep us safe but also limit our freedom of action, as we reflect the current political debate.

Laurence Tribe, a law professor at Harvard, does not mince his words. In an email sent to a New York Times columnist, stating that Donald Trump …

… has systematically eroded the norms and the institutional guardrails that initially set boundaries on the damage he and his now more carefully chosen loyalist enablers are poised to do in carrying out the dangerous project to which they are jointly committed.

The same New York Times article quoted Julie Wronski, a political scientist at the University of Mississippi, this way:

The question is how much the Supreme Court presidential immunity decision will undermine institutional guardrails against Trump’s anti-democratic behavior. If there are no repercussions for his role in the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, intimidation of election officers, and casual handling of classified materials, then Trump will be emboldened to partake in such activities again.

The two “Supremely unhappy” court decisions I recently highlighted are among the events that suggest that legitimacy is slipping away from public institutions, the legitimacy that arises, in the sociologist’s use of “institutions”, when people simply assume – take for granted – that the system is fair (Greenwood, Suddaby, & Hinings, 2002). What’s worse is when guardrails fall away and corruption becomes normalised, accepted, and institutionalised in the place the rule of law has vacated (Ashforth & Anand, 2003).

Institutions constrain us; that is, they impede us mentally from doing things that society doesn’t generally accept, like driving sensibly and not veering over the central line in a two-line highway – or prevent us from falling off the cliff on the other side. In so doing, they also enable us to do things that society sees as beneficial, making it easier to stay on a safe path. They limit freedom, yes, and in so doing protect us from other forces that might limit our freedom even more.

Until they don’t. They also prevent us from playful experimentation that might just offer us – and society, after a period of adjustment – to have better, more fulfilling lives.

The rule of law exists when an institution – the laws themselves, those who make and enforce the laws – accept that the law pertains to themselves as well as others. Laws often work better when they build in some flexibility, a guardrail with a bit of bounce, ones able to absorb a bit of the shock of collision without endangering its own foundations. There’s a danger too when the guardrails are too tightly fastened, when institutionalisation is too rigid, causing more damage in the lesser infractions.

There are two important forms that legitimacy takes, however. There’s cognitive legitimacy, usually a good form, unless our cognitive functions are deceived or we come to think that the strange, distorted rules themselves are legitimate, as when corrupt practices become the new rules.

The other type is moral legitimacy (Suchman, 1995). It kicks in when the combination of moral signals – thoughts about the consequences, the imperatives of caring for the welfare of others, and of leading a life of virtue – tell you something is messed up and nag you to do take a different path. A path that rejects a bad rule. Seeking moral legitimacy is itself a guardrail against institutionalising wrongdoing.

The political theorist John Campbell writes:

America’s political institutions are the guardrails preventing our democratic system of government from plunging over the cliff into autocracy. But their durability and strength are not guaranteed, particularly when someone like the president of the United States – perhaps the most powerful person in the world – attacks them (Campbell, 2022, p. 1).

Perhaps it’s just nostalgia for simpler days that makes me long for institutions that were more rigid, more nearly taken for granted. But in simpler days, things may have been too simple. As Albert Einstein didn’t quite say, things should be as simple as possible, and no simpler. [For what he did say, look up Einstein (1934).]

Let’s return, for a moment, to the Alps and Switzerland, where Einstein wrote his most famous theoretical papers:

You know that having gone up the mountain, you have to come back down. Dangers above and below. You’re grateful for the guardrails on the other side. You reflect that lot of mountains in Afghanistan don’t have them. Or warnings about falling cows. No wonder Switzerland is the safer place.

Ashforth, B. E., & Anand, V. (2003). The normalization of corruption in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 1-52. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25001-2

Campbell, J. L. (2022). Institutional Guardrails. In Institutions under Siege: Donald Trump's Attack on the Deep State (pp. 1-28). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Einstein, A. (1934). On the Method of Theoretical Physics. Philosophy of Science, 1(2), 163-169.

Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58-80. doi:10.2307/3069285

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571-610. doi:10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080331

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Te2X!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51c6c618-ff5a-481b-b4e2-28047c606ca8_990x369.jpeg)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)