Of ‘somewhere’, ‘anywhere’, hillbillies and home

Publication of a new book unleashed a small flood of thoughts about governing, authenticity and what it means to feel at home. Indulge me. Wade with me through that flood and see where we come out in the end:

Years ago – maybe twenty-five of them – I met the founding editor of the British political magazine Prospect. He was seeking fresh investment in the publication. A mutual acquaintance thought I might be able to help. I wasn’t, not on the scale the magazine needed. But David Goodhart impressed me.

Then, years later – maybe eighteen of them, after he had left the magazine – he published a book that claims to identify the underlying reason for Britain’s exit from the European Union. The Road to Somewhere (Goodhart, 2017). I read it. It struck a chord. Britain had become a country split down the middle, he wrote, not by left and right, not by race or ethnic background, but by a simple distinction:

One group (or should I say “we”?) were people who could feel comfortable living anywhere, we are cosmopolitans, in a non-technical sense of the term.

The others were people who belonged to a community as lifelong members. People with roots. People from somewhere.

I read the book. It made sense. It still makes sense, even now that we know the consequences of Brexit, even if we both (the “we” from “anywhere” and “they” from “somewhere”) haven’t changed our minds.

Now there’s an election underway in America, where I grew up. The country is split, not down the middle, but with its coasts against the centre. It’s not as simple as that, or as a split as somewhere/anywhere. And maybe Goodhart’s split wasn’t as simple as it seemed, either. But there’s something in that analogy. Look at the vice-presidential candidates:

There’s Tim Walz for the Democrats. A schoolteacher and football coach, a man with deep roots in Minnesota. A Midwesterner, late middle-aged. Everyone’s grandfather and high school principal.

And there’s J.D. Vance for the Republicans. A Midwesterner, early middle-aged. He shot to fame by writing a memoir about his roots in Ohio, or rather how he pulled himself up by the roots from the slough of despond of a childhood of poverty and neglect, of drug addiction among the family and neighbours. A stint in the military (as a journalist, not a combatant), then Yale Law School, then Silicon Valley, did that. Then an author. Now a US senator and Donald Trump’s choice for vice president. Everyone’s success story, or rather the story of a success that a lot of folks might wish they had.

Vance’s book is called Hillbilly Elegy. It caught my attention when it came out in 2016, but I didn’t get around to reading it. (I still haven’t.) A bestseller. A movie version followed. (I haven’t watched it.) It sounded too good to be true. (I was a bit jealous.)

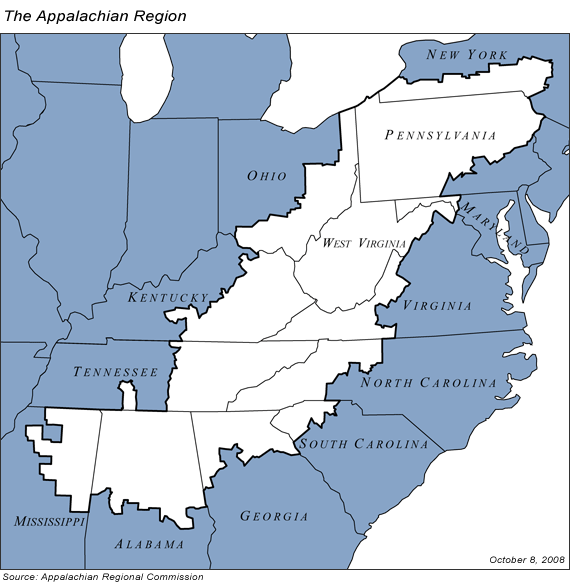

Why it caught my attention is this: When I was a student some fifty-odd years ago, I spent a lot of time at university with three professors, two of whom qualified for the label “hillbilly”. One came from Kentucky, the other from the Smokey Mountains part of western North Carolina, both parts of America known as the heartland of Appalachian music. Theirs is a place with romantic appeal, an appeal bolstered by the way that’s been neglected throughout American history.

We formed a band to play old-timey country music, an early, less energetic but more contemplative musical form than bluegrass. We called ourselves the New Bethel Tabernacle Drive-In Church. The two hillbillies gave the band its authenticity, as well as its tunes. All I added was a rather poor guitar and faulty harmonies. But those two men and their music gave me an appreciation of what it meant to grow up being ignored by city folks like me. I appreciate that – and them – to this day.

But Ohio – even Middletown, Ohio, where Vance grew up – isn’t hillbilly country. First, it’s in the Midwest, not the South. Second, the land around Middletown is pretty flat, barely a hill to be seen. So why call your story Hillbilly Elegy other than to appeal, deceptively, to an electorate you might want to help you get into political office, a Senate seat, maybe, once your name was well known?

I’m not the only person to question the author’s authenticity. In an interview with a British newspaper, the novelist Barbara Kingsolver was dismissive of Vance. She grew up in Kentucky and often writes about life in the South. She knows a fair bit about hillbillies. Along with a lot of other awards, she won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for her novel Demon Copperhead, which, like Hillbilly Elegy, tells a story of childhood poverty. But hers is set in hillbilly country. “He can tell his story,” she told the interviewer for The Times. “I’m not especially interested in it, because there are things I don’t trust in there, but he doesn’t get to speak for my people.” Vance, she said, didn’t write about the reasons why kids grow up that way, “the history of the region’s exploitative farming, mining and opioid prescriptions”.

So, what’s “home” then? Where is somewhere? These days, Kingsolver may well feel at home pretty much anywhere. She spent some of her early years in what’s now the Democratic Republic of Congo with her missionary parents, and she’s been to a lot of other places. But she speaks as though there is a home somewhere, somewhere in the central or southern parts of Appalachia if not a single, small town in Kentucky.

Walz clearly has a home in Minnesota. If he gets to Washington, my guess is he will feel out of place. The White House won’t be his home. It’s probably not anyone’s.

Vance is pretty clearly someone from somewhere, but in the sense of being not just from but away from. And it’s not the place where his book says he’s from. But he’s not – not yet, anyway – someone from Goodhart’s anywhere. The history of the changes in his name gives evidence of uprooting from the home of his early years.

And me? I’m away from Chicago, a long way away. I might be one of Goodhart’s people from anywhere, though perhaps just from nowhere in particular. A meanderer.

The book that started this particular meander?

Camilla Cavendish reviewed David Goodhart’s new book, The Care Dilemma, in the Financial Times.

I’ll read that someday, too. I chair the board of a large social care provider in Britain, looking after vulnerable adults who will never have the chance to go to Yale and Silicon Valley, or to play high school football, or even visit the White House. Maybe Goodhart will teach me something about them. Or about the system, try as it may, that doesn’t serve them well. Perhaps that will yield another story of …

Goodhart, D. (2017). The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics. London: Penguin.

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Te2X!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51c6c618-ff5a-481b-b4e2-28047c606ca8_990x369.jpeg)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)