Of ‘crooked timbers’ – and crooks: Part 1, political governance

My father was a carpenter, and during the summers of my teenaged years, I often went to work with him … Hold that thought. We’ll come back to it.

So, we have a convicted criminal running for the White House (the current state of play, but awaiting sentencing and pending appeals), and facing other trials and threatening tribulations. Given the nature of the acts that prompted the crime, the governance metaphor that comes to mind is one of foxes and hen houses. What should we make of this? Of this tale of a crook and the house he is intent on (re)occupying?

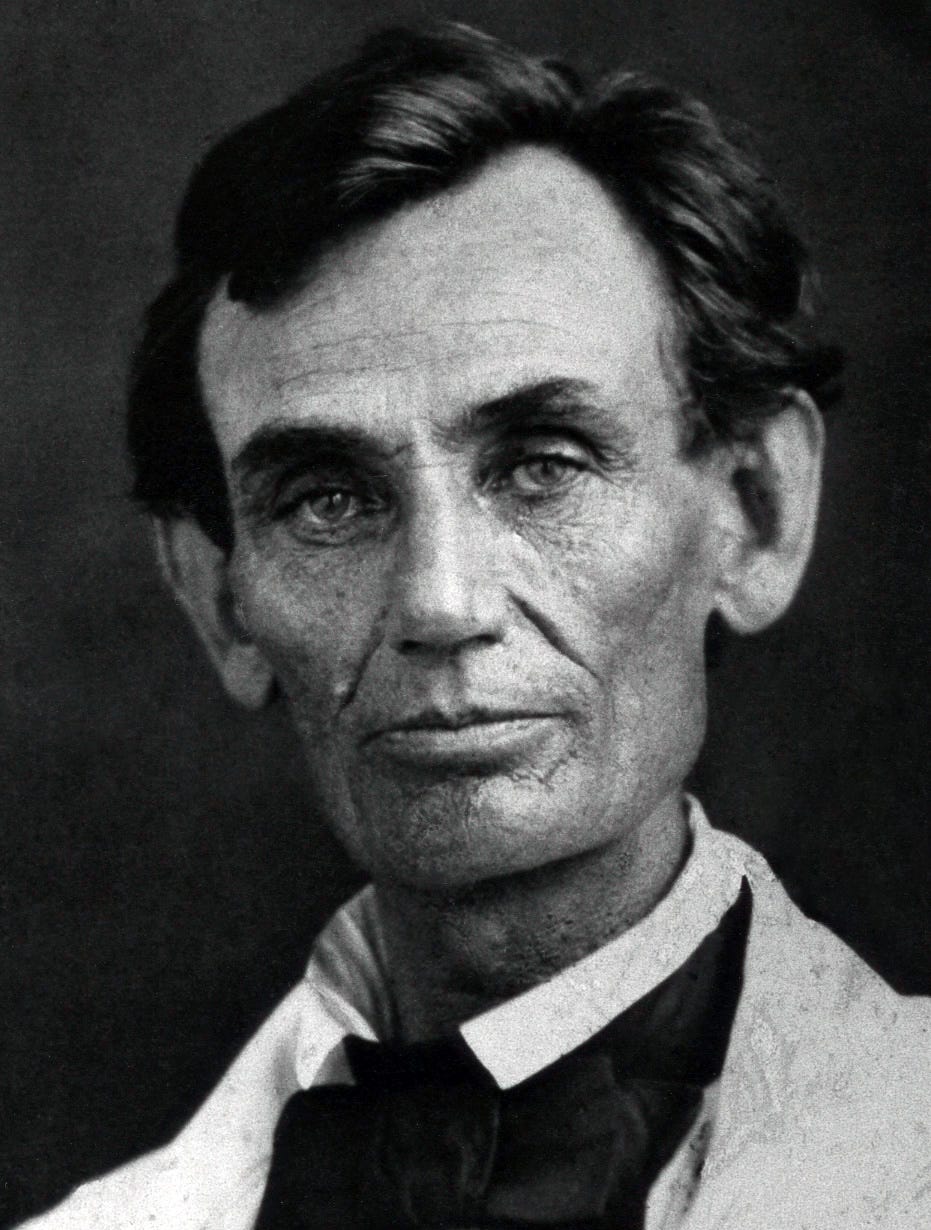

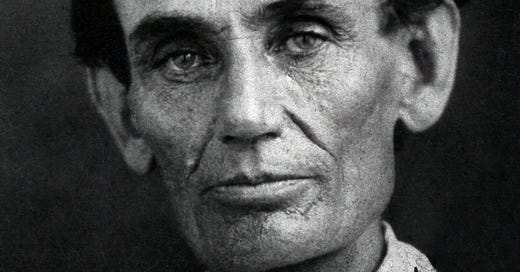

One arresting version comes in Helen Cox Richardson’s wonderful Substack post in Letters from an American, on May 23, 2024, in which she thinks about a different metaphor of houses, evoking grand plantation houses and the dismal slave quarters outside, and what that meant for American democracy. She reflects on the contrast between the Republican Party’s first candidate for president and the current one, citing Abraham Lincoln’s famed “House Divided” speech of June 16, 1858.

Richardson writes that the speech, “is often described as defining the difference between the North, based on the idea of free labor, and the South, based on enslaved labor, and the idea that one or the other must prevail,” in which Lincoln “details a long-standing plan to destroy American democracy.” The speech itself says:

[W]hen we see a lot of framed timbers … which we know have been gotten out at different times and places and by different workmen – Stephen, Franklin, Roger and James, for instance – and we see these timbers joined together, and see they exactly make the frame of a house … we find it impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin and Roger and James all understood one another from the beginning, and all worked upon a common plan or draft drawn up before the first lick was struck.

The four names were not chosen at random, as Richardson points out. Lincoln’s “Stephen” had the surname Douglas; “Franklin” was Pierce; “Roger” was Taney; “James” meant Buchanan.

Buchanan was president at the time;

Taney was the chief justice of the Supreme Court, who the year before wrote the dreadful Dred Scott v. Sandford decision;

Pierce had been president just before Buchanan; and

Douglas became Lincoln’s opponent in the 1860 election campaign.

All four were involved in reinforcing slavery, in one way or another. The “house” they framed may have been made of timbers cut at different times but to a single specification.

Richardson’s account also brings to mind a different metaphor, one of crooked timbers, the phrase that the philosopher Isaiah Berlin made popular, though its roots reside with Immanuel Kant.

In a speech and then paper published in his book The Crooked Timber of Humanity, Berlin quotes Kant to this effect:

No more rigorous moralist than Immanuel Kant has ever lived, but even he said, in a moment of illumination, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made.” To force people into the neat uniforms demanded by dogmatically believed-in schemes is almost always the road to inhumanity. We can do only what we can: but that we must do, against difficulties (Berlin, 1988, p. 17; 2013, pp. 19-20).[1]

Being human involves plural values, some of which are incommensurable and incompatible (Aarsbergen-Ligtvoet, 2006). Humanity, by implication, involves working with crooked timbers, finding a way to get along, despite differences.

My father was a carpenter, and during the summers of my teenaged years, I often went to work with him, helping him repair a rotting staircase, replace a window frame, erect a partition wall, frame a dormer window in someone’s attic. We’d go to the lumber yard – a common feature of the commercial landscape in 1950s and 1960s America – and buy the timbers we needed for each job. Dad always looked for the straightest ones he could find, and those with the fewest knots. Knots, he explained, were points of potential failure in any structure, places where water damage was most likely. Best to avoid them. If you can. Sometimes you can’t, except by spending more time and money than the client was willing or – for Dad’s clients – able to pay. “Let’s do the best we can,” he advised, instructed.

This was in Chicago, in Illinois, the “Land of Lincoln”. It had also been the land of Stephen Douglas, of course, and Chicago was the city that Martin Luther King called the most segregated in the United States, and with good reason and much evidence. It was a city of crooked politics as well. And, famously, for having been the home of the archetypal crook, Al Capone.

Dad often had to visit two or three lumber yards before he could find timbers that were straight enough to use. He tried to avoid the merchants who specialised in crooked ones. But sometimes he had to make do, to work around the crooks in the timbers available at the time.

“Do the best we can.” This is a lesson from I learned indirectly from Abraham Lincoln. And in later studies from Isaiah Berlin. And directly, in those formative years, from Dad. Happy Father’s Day, yesterday.

No doubt we’ll explore this subject further as this election campaign proceeds.

Aarsbergen-Ligtvoet, C. (2006). Berlin’s Value Pluralism In Isaiah Berlin: A Value Pluralist and Humanist View of Human Nature and the Meaning of Life (pp. 11-40). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Berlin, I. (1988). The Pursuit of the Ideal. Retrieved from https://isaiah-berlin.wolfson.ox.ac.uk/sites/www3.berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/files/2018-09/Bib.196%20-%20Pursuit%20of%20the%20Ideal%20by%20Isaiah%20Berlin_1.pdf

Berlin, I. (2013). The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas (Revised, 2nd ed.). Princton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[1] Kant's Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte in weltbürgerlichter Absicht (1784): “Aus so krummem Hölze, als woraus der Mensch gemacht ist, kann nichts ganz Gerades gezimmert werden” (see Kant's Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. 8, 1912, p. 23).

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Te2X!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51c6c618-ff5a-481b-b4e2-28047c606ca8_990x369.jpeg)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)