How shareholder interests diverge and unite – and confuse

Before moving into academic work on governance, I spent a lot of time with investor relations officers at companies in several countries in Europe, listening to their frustrations about reading the runes of sentiment from often cryptic questions from fund managers. Much has changed in recent years: the seemingly inexorable rise of private equity, the increasing dominance of passive, index-tracking funds, the decline in influence of pension funds as direct investors, not to mention the increasing consolidation of industry after industry in the hands of a decreasing number of larger companies.

I’ve been asked to give a brief talk to an international conference on research in corporate governance coming up in September, in London. It is part of a panel discussion on investors and the role they play in governing corporations. Here’s a draft of what I think I’ll say:

Corporate governance, viewed from the company side, is a dynamic with three elements: ethics, politics, and institutions. I’d like to focus today on the politics and specifically on the relationship, or should I say, the relationships between investors and companies. Recall for a moment the case of ExxonMobil and Engine No. 1, the industrial whale that in 2021 choked on the investment minnow.

Much of the academic literature on corporate governance treats “investors” as a block, a single type of actor whose actions are guided by common or even universal motivations: foremost, creation of shareholder value. Numerous studies in numerous markets have used the presence of institutional investors as an independent variable that might determine some aspect of firm performance, or perhaps moderate the influence of another one. I fear they miss the point.

Others, looking at the investment industry itself, don’t make that mistake. They look at the growing variety of fund types: traditional ones, like mutual funds, insurance companies, asset managers; hedge funds; sovereign wealth funds; private equity firms. They come with geographic markers, too; the simplest and perhaps most common is domestic and foreign. Then there’s the distinction between them based on their investment philosophy: Are they index-trackers, that is, passive funds, or stock-pickers, the actively managed ones? These characteristics capture some of the richness of the field. For researchers, they have the virtue of involving data that can be collected with ever having to leave our desks. But I fear that from a company’s viewpoint they too miss the point.

A couple of decades ago I was working – real work, not that academic stuff – in the scantly studied area of investor relations, as a consultant to companies. Investor relations officers were my customers. Most were puzzled by the way institutional investors of any type interacted with their companies’ senior management. Investors certainly weren’t the single herd stampeding in the same direction. But they also didn’t act consistently by any of the elements of the typologies commonly discussed.

Long conversations with the investor relations people – and then other long ones with people in fund management organisations – suggested there a better way of thinking about investors. I call it the shareholder stance, and it has at least three dimensions that are relevant to the companies in which they invest.

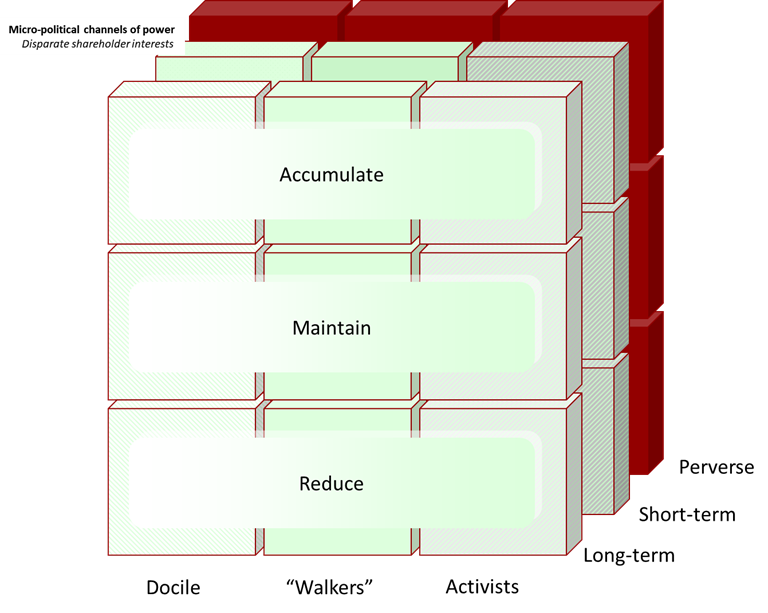

First, on any given day, hour, minute an investment manager will be inclined to one of three actions towards any given stock: buy, sell, or hold. In the language of markets: accumulate, reduce or maintain. That’s the easy one. Let’s call it their Attitude.

Second, each firm will in general relate to companies in one of three ways: by talking about issues, by selling shares, or by doing nothing at all. Activists, Walkers, Docile. Let’s call that their Participation.

Third, as a matter of general disposition towards its portfolio, a fund will tend hold shares for a long time, or to trade frequently, or do something that is either against the company’s interest, or possibly, accidentally, against its own best interest. I call it their Horizon: long-term, short-term, or perverse.

Perverse investors include short-sellers, betting that the stock is going to fall, but for the moment, they have legal ownership of the shares and thus the voting rights, should a vote be pending. Other perverse investors aren’t stupid. They are just hoping that the short-seller are wrong, so they lend shares to the short-sellers and earn interest in the meantime.

This three-by-three matrix yields 27 stances that an investor might take when deciding what to do about any individual investment.

Now recall again Engine No. 1 and Exxon. Its horizon was short-term, its attitude was to sell soon and move on, and its participation was activist. Its small shareholding meant management could just ignore it. But in 2021 this little upstart, environmentally-minded fund managed to get three dissident directors elected to the Exxon board. How could that happen? It built a coalition of the willing. On the “Participation” dimension, several were docile or walkers but, for varying reasons, decided to become activists on the day. Their attitude was to “maintain” their position but not business as usual. Many had a long-term horizon but decided for this stock and on the day they wanted to maintain their positions. Some might have been partially perverse, having loaned shares to short-sellers, while continuing to own part of their original position and thus still able to vote. They joined with Engine No. 1, a firm prepared to short the stock and potentially with backed by the power of docile, long-term, maintain-oriented funds.

I say “potentially” because the investor relations officers probably didn’t know what was happening at all. Few investment firms I know of would tip their hands to the companies in which they invest. As a result, investor relations officers and corporate senior managements can be hoodwinked when a coalition forms seemingly out of the blue.

One lesson is this: Thinking of investors as a monolith is woefully inadequate to describe the complexity of investor behaviour. A second is that more subtle categories of investors may be better, but they can still mislead. A third is that this model of the shareholder stance might be a useful tool for investor relations officers in anticipating the outcome of votes from afar.

Another is this: coalitions built on issues don’t necessarily mark a permanent realignment. Members one year might have a different “Attitude” towards a stock the next time. They might have jumped out of the short- and long-term “Horizon” into the perverse zone, but having supported a short-seller and lost the right to vote, for a while. They might have sensed the way the political winds are blowing – when the politics of their end-investors or the national level debate and decide that on “Participation”, walking might be more pragmatic than being activists. After all, walking, too, can be a quiet form of activism (Admati & Pfleiderer, 2009).

It is confusing, and not just for companies. Just ask Engine No. 1, three years after its Exxon “success”.

I welcome your comments, here, or privately.

Admati, A. R., & Pfleiderer, P. C. (2009). The 'Wall Street Walk' and Shareholder Activism: Exit as a Form of Voice. Review of Financial Studies, 22(7), 2645-2685. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhp037

Nordberg, D. (2010). The Politics of Shareholder Activism. In H. K. Baker & R. Anderson (Eds.), Corporate Governance: A Synthesis of Theory, Research, and Practice (pp. 409-425). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Te2X!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51c6c618-ff5a-481b-b4e2-28047c606ca8_990x369.jpeg)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)