Fools all? Checks, balances, and the separation of person from office

On Trump, immunity, and the Supreme Court

The phrase “checks and balances” describes the separation of powers often regarded as the antidote to tyranny in any system of governance. The ideas stem from the writings of Charles, Baron Montesquieu, and perhaps from John Locke, in the early to mid-18th century (see Vile, 1998, Chapter 4). With the adoption of the US Constitution later in that century, the ideas became manifest in the American experiment with democracy.

So successful was the theory (i.e., Montesquieu, Locke) when put into practice (the Constitution) that it became the central to the argument of correcting the agency problem in corporate governance. It is now codified in many jurisdictions around the world. Independent directors hold the keys to the audit committee’s work as a check on the power of chief executives, and shareholders hold the keys to the boardroom itself. (I’ll return to this theme in another post, soon.)

Even the Russian and Chinese systems of corporate governance accept them. The systems of political governance in those countries may not bow down before that principle, but they nod to it in the search for political legitimacy.

A question before the US Supreme Court now, however, can be seen as a test of the robustness of the theory when faced with a puzzle not specifically considered by Montesquieu or Locke and not mentioned explicitly in the US Constitution: Between the three, notionally co-equal branches of government, what stops the president from doing whatever s/he wants?

The historian and Substack writer Helen Cox Richardson reported on the case by highlighting this commentary about Donald Trump’s petition for immunity from prosecution, which was aired at the Supreme Court on April 25:

“I am in shock that a lawyer stood in the U.S. Supreme Court and said that a president could assassinate his political opponent and it would be immune as ‘an official act,’” lawyer Marc Elias, whose firm defends democratic election laws, wrote today on social media. He added: “I am in despair that several Justices seemed to think this answer made perfect sense.”

Elias was referring to the argument of Trump’s lawyer before the Supreme Court today that it could indeed be an “official act” for which a president should be immune from criminal prosecution if “the president decides that his rival is a corrupt person and he orders the military or orders someone to assassinate him.”

Whether it did make “perfect sense” to even some of the justices is (at this writing) still a moot point. It will be until the court rules. And Elias overstated the problem. The US Constitution, in its separation of powers, does place Congress as prosecution (House of Representatives) and jury (Senate) in the case of presidential malfeasance if office. Central to Trump petition to the Court is that the House impeached him for his actions on January 6, 2001, and the Senate acquitted him. The check has already produced the balance, Trump’s supporters might argue. The Constitution doesn’t give the Court any role in such matters.

The argument I haven’t heard yet in the discussion is a different one, however. Trump was in office in the time between losing the November 2020 election and leaving office in the third week of January 2021. But was everything Trump (the person) did during that time the work of Trump (the president)? In contesting for election and in disputing the election results, wasn’t Trump acting not as president, but as candidate. In standing for election and not sitting down after it was over, wasn’t he acting as a private citizen in pursuit of public office, not as an officer of the public?

The intent of the founders in writing the Constitution was 1) to check the power of the Presidency by creating a balance through the Legislature, and not through the Court, whose membership a sitting president might expand to meet that person’s expediencies, and 2) the balance powers by protecting the Presidency from wilful prosecutions?

If that’s right, then shouldn’t we also consider that Trump was president – but not the Presidency. There’s nothing in the Constitution to protect the candidates for office. Candidates are subject to the rule of law, like everyone else.

But let’s remember, too:

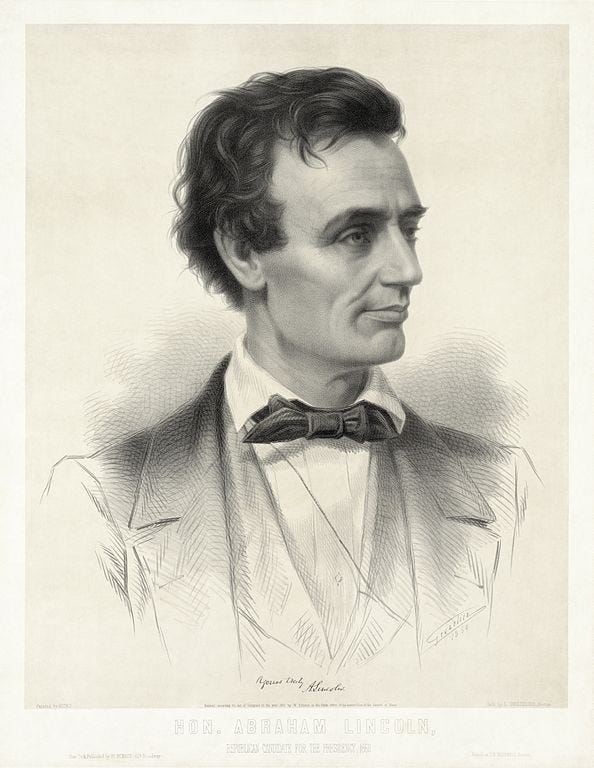

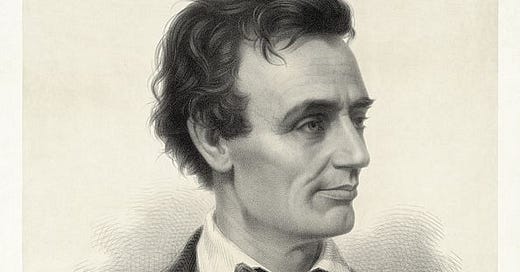

During a speech in 1858, as he mulled a campaign for the Presidency as the newly founded Republican Party’s first candidate, Abraham Lincoln may have said: “You can fool some of the people all the time and all the people some of the time, but you can't fool all the people all the time.”[1]

But that doesn’t matter, does it? In practice, not theory, what you need to do is fool just less than half the people, in the right states, one day every four years. Or five of the Supreme Court Justices once in a lifetime. That’s the practice, not the theory. It’s …

Vile, M. J. C. (1998). Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Online Library of Liberty.

[1]Or maybe it was P.T. Barnum, promoter of what became the Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus (ibid.). Or Bob Marley.

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Te2X!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51c6c618-ff5a-481b-b4e2-28047c606ca8_990x369.jpeg)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)