Directors and their decisions on the threshold

Boards sit at the apex of the organisation. Through their collective decision-making, directors take legal responsibility for the outcomes and the processes. And when things go seriously wrong, someone is sure to ask: “Where was the board?” (MacAvoy, 2003), as we can suspect that the directors of the UK Post Office have been doing. The directors of Fujitsu – the supplier of the faulty software the Post Office used, certainly have been. But at least some the individuals who sit on corporate boards – the so-called nonexecutives – sit outside the day-to-day flows of information required for evidence-based decision-making and separated from the insights to be gathered from the nuances of corporate culture. Moreover, many are only involved part-time with the business. That brings benefits, of course, but it also raises questions about their commitment to collective aims.

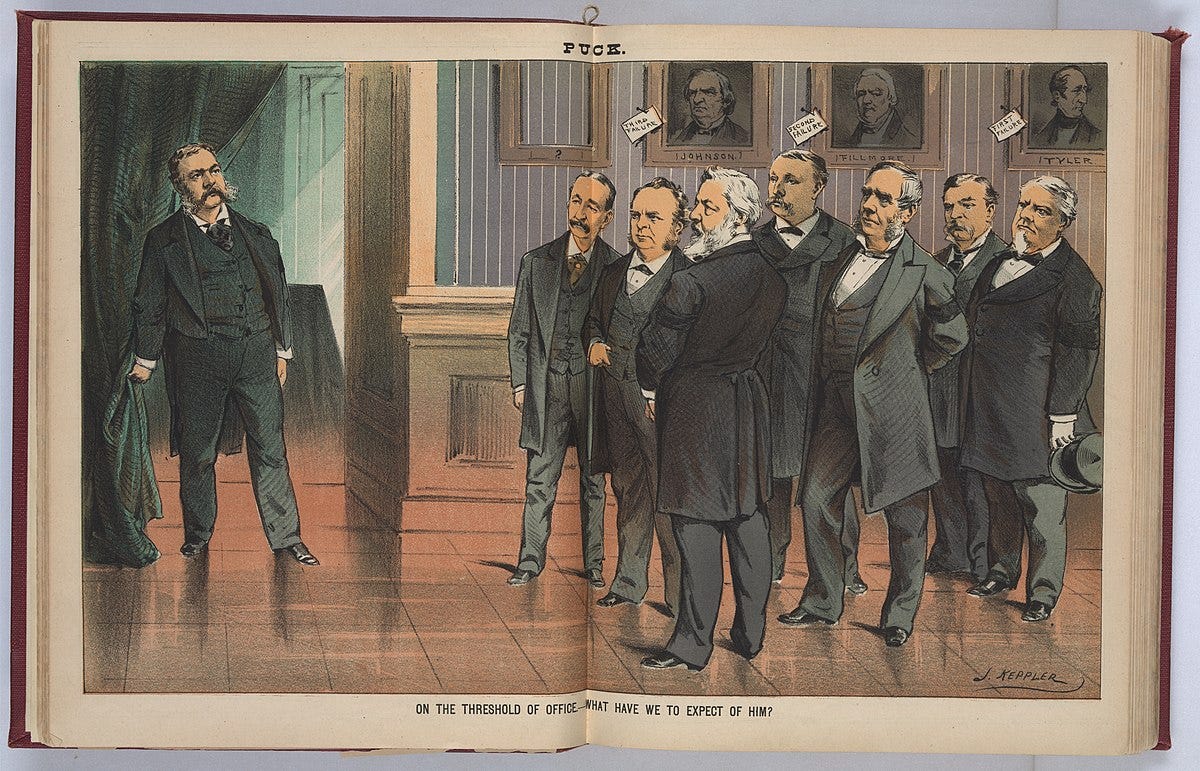

In the unitary boards common in Britain, where executives sit alongside the outside, nonexecutives, those executives are asked in law and codes of conduct to set internal allegiances aside when working on board business. That is, directors – especially but not only the nonexecutives – are liminal actors in the workings of corporations, neither inside nor outside. They perch on the threshold between the organisation and the outside world of shareholders and stakeholders. When important issues require decisions, how do these outside-insiders, or inside-outsiders decide, with what degree of commitment, and with what sense of purpose? Under these circumstances, in what ways is director stewardship likely to emerge?

You could run a few thought-experiments to find a way through that thicket. Or you could read the ones I conducted in a paper written for a research handbook on decision-making on boards (Nordberg, 2022). One concerns deciding on a merger and the second dislodging an incumbent CEO. The third looks at whether to pay a dividend ahead of a major investment that requires new capital. The fourth comes when a crisis – let’s say a pandemic – disrupts the best laid plans. Those scenarios give us the tools to reflect on how to govern.

The argument that paper makes is not a manifesto to do away with structures and mechanisms of corporate governance. There is little doubt that governance of corporations – and indeed many other organisational forms – has become more thoughtful over the 30-odd years since the Cadbury Code restructured the work of boards. Instead, I argue that directors need to pay more attention to the paradoxes of being a director and the puzzle they create for directors when they make major decisions. Piecing together theoretical approaches and empirical evidence, the paper presents a tentative model of a path from liminality to psychological ownership that seems an antecedent of director stewardship.

The book that contains that exercise is behind a paywall, though many academic libraries have a copy. But you can find a manuscript of version of my chapter online.

[And, yes, I know the picture is a political cartoon, not a depiction of a corporate board of directors. But the boundaries between states, markets and corporations are becoming awfully blurred.]

MacAvoy, P. (2003). ‘Where Was the Board?’ Share Price Collapse and the Governance Crisis of 2000–2002. In P. MacAvoy & I. Millstein, The Recurrent Crisis In Corporate Governance (pp. 66-94). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nordberg, D. (2022). Liminality, purpose, and psychological ownership: Board decision practices as a route to stewardship. In O. Marnet (Ed.), Research Handbook on Corporate Board Decision-Making (pp. 41-62). Cheltenham, Glos.: Edward Elgar.

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Te2X!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51c6c618-ff5a-481b-b4e2-28047c606ca8_990x369.jpeg)

![How to govern [not like that]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!emEQ!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9d7f587-4c16-42f0-9526-b00edc0ab4c8_155x155.png)